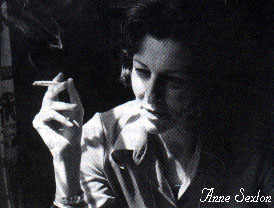

"I don't read poetry, but I read Anne Sexton."-- A fan, 1985

ANNE SEXTON

From a Biography by Diane Wood Middlebrook

Liked to arrive about ten minutes late for her own performances: let the crowd work up a

little anticipation. She would saunter to the podium, light a cigarette, kick off her shoes, and in a throaty voice say,

"I'm going to read a poem that tells you what kind of a poet I am, what kind of a woman I am, so if you don't like it you can leave." Then she would launch into her signature poem,

Her Kind:

"I have gone out, a possessed witch... A woman like that is misunderstood... I have been her kind."

What kind of woman was she?

Spirited, good-looking: tall and lean as a fashion model; a suburban housewife who called herself Ms. Dog; a daughter, a mother; a New England WASP; like Emily Dickinson, "half-crack'd."

And what kind of poet?

Intimate;confessional; comic; insistently, disruptively female; a word wizard; a performance artist; a crowd pleaser.

Those were some of the things you could learn during her first fifteen minutes on stage.

Some people didn't like the Sexton persona.

But behind it stood a serious, disciplined artist whose work had been admired from the beginning by distinguished peers.

During her eighteen years as a writer, Sexton earned most of the important awards available to American poets. She published eight books of poetry (leaving others in manuscript), and

she saw her play Mercy Street produced off-Broadway. She was a shrewd businesswoman, and she became a successful teacher; though skimpily educated, she rose to the rank of professor at Boston University, teaching the craft of poetry.

She conducted this career in the context of a mental disorder that eluded diagnosis or cure. Suicidal self-hatred led to repeated hospitalizations in mental institutions.

She became addicted to alcohol and sleeping pills. By the time she committed suicide in 1974, misery had hollowed her out and drinking had obliterated her creativity.

Yet from the rising of Anne Sexton's star in 196o, with the publication of To Bedlam and Part Way Back, hers had been an important new voice in American poetry.

Her maladies did not wholly succumb to insight: although psychotherapy helped her dramatically, she stayed sick. Yet her poems invented a self that others valued, and this endowed her real life with opportunities.

Sexton wrote about the social confusions of growing up in a female body and of living

as a woman in postwar American sodely. Thousands of women have shared the mental

disorders thal disabled her, and hundreds of thousands have shared her dissatisfaction with

life as a suburban housewife, but few possess the gift, or summon the discipline and

courage, or make the friends, or command the financial resources, or have the well-timed

good luck that made Anne Sexton into a serious poet. That is why, in representing the

relationship between her illness and her art, I have attempted to avoid the perspective of a

pathography.

Sexton's life ended in a suicide that was the act of a lonely and despairing

alcoholic, but it might have ended silently and and much earlier if she had not, almost

miraculously, found something else profoundly important to do with it.

Last updated on March 9, 1998

To return back to the colder than snow introduction page.